What Coffee Clarity Means in the Cup

Learn what coffee clarity means in your cup and how to achieve it. Discover the factors that affect coffee clarity and improve your brewing skills.

Clarity in tasting terms means whether the elements in a drink are obvious or muddled, not how see-through the liquid is.

When you read tasting notes on a bag and see fruit, caramel, or cocoa, those terms reflect how distinct the flavors are in the cup. Good clarity lets you pick out single notes instead of a single generic impression.

Perception combines taste and aroma. A simple framework of four categories — fruit, sweet, savory, bitter — helps home brewers judge what they detect without fancy vocabulary.

This guide focuses on practical levers you can control at home: grind, brew time, water temperature, filtration, and roast profile. Small tweaks often shift a brew from muddy to bright.

Expect repeatable, low-drama steps aimed at home brewers in the United States and quick checks to diagnose muddled cups.

Key Takeaways

- Clarity describes how distinct flavors appear in the cup.

- Flavor comes from both taste and aroma; use four basic categories to assess.

- Grind, time, temperature, filtration, and roast shape final flavor separation.

- The same beans can taste clearer or muddier depending on extraction.

- Simple diagnostics and small changes can improve flavor separation at home.

What clarity means in brewed coffee (and what it doesn’t)

In tasting, separation means you can trace one flavor, then another, rather than getting a single muddled impression.

What Would You Like to Learn Next?

Choose an option below:

Flavor clarity vs visual clarity in the cup

Visual clarity is simply how see-through the liquid looks. That often misleads home tasters into equating transparency with quality.

Flavor clarity is sensory: can you detect discrete components like fruit, sweetness, and roast? They are not the same.

Separation of flavors in tasting notes

High separation makes tasting notes plausible. You might taste blackberry, then cocoa. Or you might only get “roasty and vaguely sweet” when separation is low.

“A clean acidity helps fruit pop; a soggy, harsh acid hides parts of the profile.”

How clarity relates to acidity, aroma, finish, and balance

- Aroma gives the brain early cues that help sort compounds into recognizable flavors.

- Acidity acts as a sensory feel — clean acids highlight fruit; sour or harsh acids cause muddle.

- A clean, sweet finish supports separation; a bitter, drying finish collapses it.

- Balance is the checkpoint: separation is useful only if the cup remains pleasing, not thin or sharp.

Quick tasting prompt: Sip, name the top 2–3 components (fruit/sweet/savory/bitter). Wait two minutes and sip again to see if flavors separate further in the cup.

Coffee clarity and body: tradeoffs, exceptions, and what’s really happening

Many brewers assume a heavy mouthfeel drowns out subtle notes, yet that isn’t always true.

Body and perceived flavor separation often get treated as opposites because oils, fines, and suspended particles boost mouthfeel while blurring boundaries between notes.

More surface area and continued extraction can also amplify bitterness, which masks delicate flavors. That is why methods that leave fines in the cup tend to seem muddier.

Why body and clarity are often seen as opposites

Paper filters remove oils and micro‑particles, producing a lighter mouthfeel and a cleaner profile. Metal filters and French press keep more suspended solids, increasing body.

When extraction runs long, slow‑dissolving roast compounds can muddy taste. That makes heavy body feel like a clarity loss, even when the base flavors are present.

When high body and high clarity can coexist

Real‑world exceptions prove the point. Temple Coffee’s Kenyan “Kamviu” is cited for strong body alongside bright, floral aroma and clean acidity.

Espresso shows the same idea: massive body but still assessable for separation. In practice, high body with clear flavors comes from clean extraction, balanced roast development, and good green‑bean quality—not from stripping everything away.

Next: the biggest clarity killers are usually preventable and tied to fines, extreme extraction, and roast taste. We’ll dig into those causes and fixes next.

Why your cup tastes muddled: the biggest clarity killers

A muddled cup usually starts with tiny particles and ends with bitter notes that hide fruit and sweetness.

Fines and continued extraction

Fines are the small grind particles that slip past filters. When they sit in your cup they keep dissolving, changing the balance as you drink.

This post‑pour extraction often increases bitterness and flattens flavor separation. Paper filtration or coarser grind reduces fines and stops the after‑brew shift.

Under‑extraction vs over‑extraction

Under‑extraction gives a thin, sharp sip that lacks sweetness. Over‑extraction pulls slow‑dissolving compounds and reads as bitter or drying.

Think of clean acidity as lively, fruit‑like acids that highlight flavors rather than harsh sourness. Good extraction reveals those acids, not hides them.

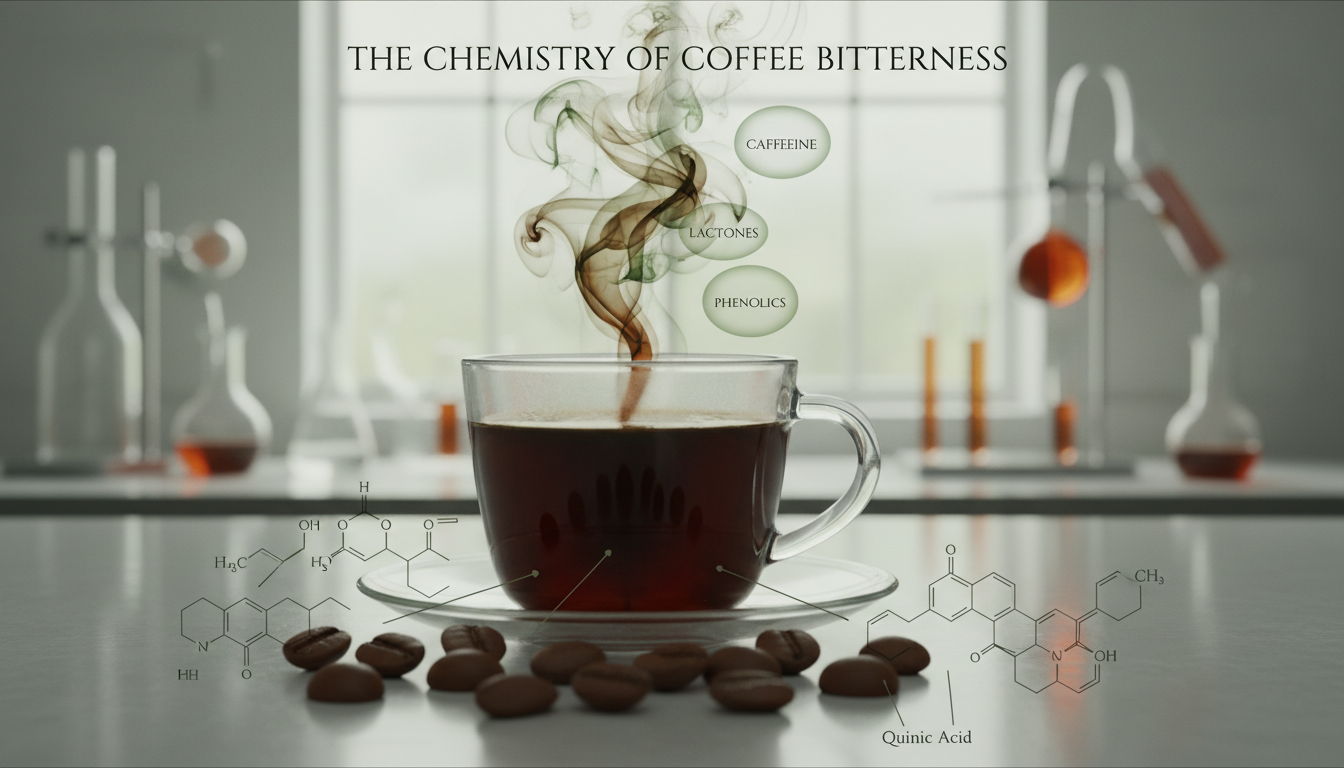

Roast development and roast taste

Dark roast caramels and sugars can taste sweet, but excessive roast character compresses origin characteristics.

Sometimes slight under‑extraction preserves separation on darker roasts because caramelized sugars dissolve slower than lighter fruit compounds.

- Dull aroma, one‑note roast dominance, or lingering bitterness are signs of muddiness.

- Fix grind and filtration first, then shorten or lengthen contact time as needed.

| Problem | Sensory Clues | Quick Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Fines | Increasing bitterness over time | Use paper filter or coarser grind |

| Under‑extraction | Thin, sharp, lacking sweetness | Finer grind or more time |

| Over‑extraction | Bitter, drying, heavy | Coarser grind or shorter brew time |

Quick flow: adjust grind/filtration → tweak contact time → reassess roast level before changing beans or gear.

Brewing methods and filters that shape clarity

How you brew strongly affects whether individual flavor components stand out or blur together. Different brewers and filters change which particles, oils, and dissolved compounds reach your cup.

Paper filter brewing for a cleaner profile

Paper filters trap oils and fines. That produces a lighter mouthfeel and makes single components easier to detect.

Use a rinsed paper filter and stable water temperature for consistent extraction. This method suits tasters who prefer crisp fruit and clear aromatics.

Immersion brewing and French press: managing sediment without losing flavor

Immersion brewing and French press give fuller body and broad extraction. They also leave more suspended particles, which can blur the cup if unaddressed.

To reduce sediment: plunge gently, pour slowly, and leave the last ounce behind. These small steps limit fines while keeping texture.

Hybrid approach: steep, then decant through paper

The hybrid method aims for both texture and separation. Steep coarse grounds about 4 minutes, then decant through a paper filter for ~90 seconds.

This preserves immersion-style development, then removes oils and fines that can muddle the profile. Try it when you want both body and precise components.

| Method | Typical Profile | Main Tradeoff |

|---|---|---|

| Paper pour-over | Clean, bright; distinct components | Light body, high separation |

| French press (immersion) | Full-bodied, rich mouthfeel | Higher sediment risk, potential muddiness |

| Steep then paper | Balanced texture with clearer notes | Extra step, but improved separation |

How to increase coffee clarity with brewing variables you can control

Start with a consistent water ratio and treat that ratio as your baseline. Pick one weight pairing and stick with it while you dial other variables. Changing ratio between immersion and filter usually confuses the process more than it helps.

Dial in grind size

Adjust grind next. Too many fines keep extracting in the cup and raise bitterness. Go coarser if the cup feels muddy or heavy.

Make the grind finer only when the brew tastes hollow or lacking sweetness.

Control contact time

Contact time is the main tradeoff: short equals sharp acidity and low sweetness; long pulls slow compounds and can mask fruit. Change only one variable at a time so you know what worked.

Use brew temperature to fine-tune

Hotter water extracts faster and can make notes pop, but extreme heat increases bitter compounds on some roasts. Use temperature as a subtle tool, not a blunt instrument.

Choose a filtration strategy

| Filter | Typical Result | Best Use |

|---|---|---|

| Paper | Cleaner separation, lighter body | When you want fruit and sweetness to stand out |

| Metal | Full body, more oils | When texture is priority and you accept some muddle |

| Hybrid / double | Balanced body with clearer notes | When you want both texture and distinct components |

Let it cool and taste again

Taste at brew temperature, then try again near 130°F. As it cools, aroma, acidity, and sweetness separate and a fruit note plus a sweet note (honey, caramel, or chocolate) should be nameable without guessing.

- Lock ratio

- Adjust grind

- Tune contact time

- Fine‑tune temperature

- Pick or tweak filter

Control what you can: consistent process and small changes beat constant gear swaps when your goal is clearer flavor separation.

Conclusion

A well‑made cup reveals separate flavor components — fruit or sugars, acidity, body, and finish — not a single muddled impression.

Lost clarity usually comes from fines, extraction extremes, or bitter overload. The simplest fixes are a locked water ratio, sensible grind changes, and a filtration choice that fits your goal.

Body and separation can trade off but need not exclude each other: clean extraction, balanced roast, and good processing often deliver both texture and distinct notes.

Train your palate: keep tasting notes, change one variable at a time, and sample again as the cup cools. For your next brew, pick a method, lock water and ratio, adjust grind to reduce fines, manage time, and use paper or a hybrid when maximum separation is the aim.

FAQ

What does clarity mean in the cup?

Is clarity the same as visual clarity or cup appearance?

How does clarity relate to acidity, aroma, and finish?

Why do body and clarity often seem opposed?

Can a cup have both high body and high clarity?

What causes a muddled, bitter, or flat tasting cup?

How do fines and continued extraction affect flavor?

How do under-extraction and over-extraction change acidity and clarity?

How does roast development affect clarity?

Which brewing methods generally deliver the cleanest profile?

How can you manage sediment with immersion methods like French press?

What is the hybrid approach to improve flavor separation?

What water ratio should I start with to improve clarity?

How does grind size affect muddiness and separation?

How important is contact time for clarity?

What brew temperature supports clarity without flattening body?

Which filtration strategies should I consider?

Should I taste the brew as it cools?

Why Cheap Coffee Often Tastes Burnt

» Discover special tips and stories about coffee